James Welton Horne was born on 3 November 1853. His mother, Elizabeth Harriet Orr had been born in England but his father, Christopher Henry Horne is more of a mystery. James Horne’s 1890 biography said his father was from Saxe Cobourg, had gone to America and later to Toronto, where he had established a woolen mill, eventually becoming a partner in Clarke Woolen Mills in Toronto. A 1906 biography omits any mention of Germany and describes the family origins as being ‘Scotch and English’.

The story goes that his father died when James was nine, and as a result of leaving almost nothing in his estate James left school to work on a farm to help support his mother and four younger siblings, moving to another farm in Pickering aged 11 where he was able to continue at school every other day until he was able to get work helping a church Minister when he was able resume full time schooling. Unusually, we haven’t been able to find any records that show when his mother or father married, or died.

At 15, his biography said, he apprenticed as a mechanical engineer for five years, leaving his salary to accumulate and then investing the resulting $3,000 in the company, (or $5,000 – even contemporary records don’t agree) and being offered a directorship at that point. He sold out aged 22, and became an insurance agent until in spring 1878 his health failed and he headed to California, but by summer was in Winnipeg (still a town of only 3,000) setting up an insurance and shipping agency, later adding loan valuation to his portfolio.

We can find James in 1871 in Whitby, shown aged 18 living with his mother, Elizabeth, (recorded as Horn). She was shown as 35, born in England, and her other children were recorded as Wilhmina, 16, Harriet, 14, Henrietta, 9 and another son Stephen who was 12. There’s no mention of her husband, Christopher Horn, but there is in the 1861 census, when the family were in Scarboro, in Ontario. Elizabeth admitted to being 29 on that occasion, but James was recorded as 11, Wilmina was 9, Harriett was 7, Stephen was 4 and Henrietta was 2. If accurate, this would suggest that all the children were older than they were shown in the 1871 census. and many subsequent records. The other intriguing fact is that Christopher Horn was shown, aged 34, born in Germany but working in the United States. That suggests he may not have been running a woolen mill in Toronto, and may not have died when James was nine (if his 1853 birth is accurate). And in 1871 James apparently wasn’t away ‘apprenticed as a mechanical engineer for five years’, but living at home and working as a carpenter.

We’ve found an Elizabeth Orr, in Ontario, in 1851, aged 18 and living with her parents, Samuel and Mary, who were from England, and farmers. There was another Elizabeth Orr who was in Ontario who had been born in England, and was aged 20. She was working in a distillery, and enumerated rather alarmingly under the heading ‘Name of Inmates’, suggesting the factory also provided a dormitory for its workers.

In 1881 it was apparent the CPR would be extended westwards, and speculation started to guess where settlements would spring up. As an 1889 publication explains: “Mr. Horne entered into an agreement with the railway company by which he was given a certain quantity of land at a fixed price, and on his erecting business buildings he was to have a rebate. He at once opened an office, or rather erected a tent on the prairie, divided his land into lots, opened and graded streets and when this preliminary work was accomplished began the erection of buildings.” He persuaded the government land agent to set up his office here, and then to get a post office, and thus the city of Brandon was established. Although his role is acknowledged in an 1882 publication “Brandon, Manitoba, Canada and her Industries”, which concludes “We may safely state that no man in Brandon has accomplished more for the welfare of the city than Mr. Horne, and in years to come he will be remembered as one of the founders of the Infant City, and a leader in laying the foundation of her greatness” the ‘remembered’ part doesn’t seem to be true as his name doesn’t appear at all on the extensive ‘Heritage Brandon’ website. He was an Alderman, the Chairman of the City Board of Works and the province made him Commision of the Peace.

With an eye to repeating his success, Horne travelled to Burrard Inlet via California in 1883, but chose not to invest yet. (He He visited again in 1884, and bought some farm land, (his arrival from Nanaimo being recorded as J W Horn). In March 1886 he moved across and started serious land purchase (although many of his investments were outside the area torched by the fire).

It would appear that Mr. Horne was married at some point, but quickly became a widower. He was certainly living alone in 1881 when he was shown aged 29, and employed as an ‘agent’. He was in Emerson, Manitoba, in 1891 as W James Horne, recorded as being single, and in Vancouver in 1901 where he was shown as widowed and a boarder with Mr Tate. In 1911 he was recorded as a widower, lodging, and for some strange reason he has added two years to his age, shown as being born in 1851. Searching the Directories of the period shows Mr Horne moving on a regular basis – and most of the time living in a hotel. And not just any hotel – at times it was the Hotel Vancouver, at others the Badminton and earlier the Leland.

Once in Vancouver J W Horne wasted no time in acquiring, and then re-selling land. As he had in Brandon, he bought land from the CPR. They had of course been given it as an incentive to bring the terminus of the line to what would soon become Vancouver. Both David Oppenheimer’s land company and the Brighouse/Morton/Hailstorm partnership who owned the West End had given the CPR hundreds of acres. Once surveyed and in some cases cleared by CPR crews, the lots were auctioned off. Horne was an avid purchaser of land, both in the Gastown area and further west in Coal Harbour. At one point his assets were said to be second in value only to the CPR themselves. (That was another exaggeration; an 1891 biography described him as ‘the heaviest individual property owner in Vancouver’, and at $156,000 he was a big-time investor, but Isaac Robinson and David Oppenheimer both had more valuable holdings.

It isn’t recorded whether he had built anything to lose in the fire, but given the timing of his arrival it seems unlikely. Once the city was rebuilding, the demand for well-located lots heated up, and as a land agent Mr. Horne had good sites to sell, and as demand rose so too did the prices. In 1887 J W Horne’s assets were assessed at $40,000. in 1889 they were worth $125,000, and in 1891 $156,000, making him the fifth wealthiest landowner in the city (and the CPR and the Vancouver Improvement Company were in the first and second spots).

This wasn’t only connected to land values rising – J W was becoming a very active developer too. It was said that “only four years after his arrival in Vancouver, Horne had built major brick blocks on most of Vancouver’s principal streets”

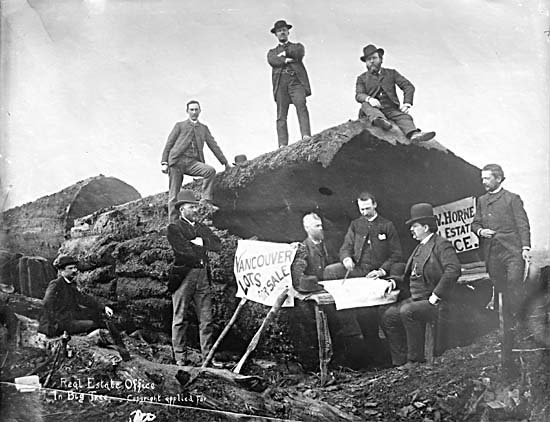

Promotion by J W Horne (standing at the table, centre) using a burned log as a prop, 1886. – City of Vancouver archives

While in Brandon Mr. Horne built property to entice new business, while in Vancouver it was just to be part of the massive growth taking place all round. In 1889 he completed a flat-iron building that backed onto the Springer-Van Bramer block on West Cordova Street.

Like Springer and Van Bramer he hired N S Hoffar as the architect. The block had elaborate cornice details and a turret (sadly, now gone) and a tiny juliet balcony on the snub point of the flatiron angle.

A year later he completed another building nearby on Cambie Street. Again, N S Hoffar was the designer. The block is unusual in having two retail floors behind the cast iron facade, with stairs up and down from the sidewalk. Among several significant tenants were the Bank of North America (1892), Rand Bros. Real Estate (1896) and G.A. Roedde, bookbinder (1896). In addition, Atlen H. Towle, architect of the First Presbyterian Church (1894) at East Hastings and Gore Avenue, had offices here. Between 1910 and 1925, several publishing and lithography firms were based here, no doubt due to the proximity of the Province and Sun newspaper buildings. The etching below shows the top floor was probably added after it was first built.

Another building still standing that can be linked to him is the Yale Hotel. Completed in 1889, designed once again by N S Hoffar, the Colonial Hotel (as it was initially called) was completed at a cost of $10,000. When completed it stood isolated from most development in the recently cleared forest near Yaletown’s railyards and lumber mills. The name the Yale was adopted in 1907 when new proprietors took over. In 1909 an addition was built to the east, designed by W T Whiteway. In 2011 a new condo block, The Rolston, was built to the south of the building with a restoration of the hotel as part of the development.

Etchings of early Vancouver buildings from West Shore magazine, May, 1889. West Shore was a magazine published in Portland, Oregon from 1875 to 1891. The building at bottom right is the Yale Hotel, which is still around. The White Swan Hotel (top left) was at 500 (West) Cordova.

J W had an additional financial operation in the city. He founded the Vancouver Loan Trust Savings and Guarantee with at least three other partners; H T Ceperley, H A Jones and R G Tatlow. Ceperley was Manager of the operation, and married to A G Ferguson’s sister. He had no money of his own but was successful at managing other peoples’ and the Daily World commented that the company bought and sold improved and unimproved real estate. He also petitioned for the Pacific Coast Fire Insurance Company to be created in 1890, and was allowed to get it up and running in 1894, with David Wilson and Edward Odlum.

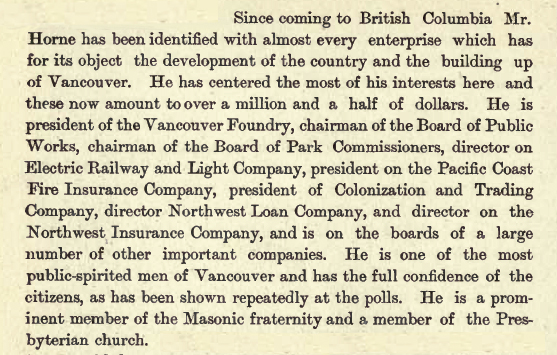

As in Brandon, Horne wasn’t content to just operate his business and make money. He stood for election as an Alderman, and topped the poll in 1889 and 1890. Horne was a keen Freemason, and was photographed in 1891 in his Masonic regalia. From 1890 to 1894 he represented the city in the Provincial Legislature, turning down offers to become a Minister because of the business he was still conducting in the city. He gave up the political representation in 1894 on medical advice. An 1890 publication listed his many interests.

As in Brandon, Horne wasn’t content to just operate his business and make money. He stood for election as an Alderman, and topped the poll in 1889 and 1890. Horne was a keen Freemason, and was photographed in 1891 in his Masonic regalia. From 1890 to 1894 he represented the city in the Provincial Legislature, turning down offers to become a Minister because of the business he was still conducting in the city. He gave up the political representation in 1894 on medical advice. An 1890 publication listed his many interests.

Not bad for someone who had only arrived four years earlier. His philanthropy included establishing and personally paying for the Stanley Park zoo. His business interests in the year following publication of the list above included creating an instant town that would become the District of Mission.

He identified the location, as he had in his earlier real estate ventures, as a prime target, in this case because it was about to gain the only Canada/US railway junction in BC, meaning that anyone wishing to travel to or from the United States would have to pass through Mission. He invested tens of thousands of dollars building a model city, and then advertised a grand auction across North America.

The Mission museum tells the story “As a land developer and businessman, James Welton Horne had erected the city of Brandon by a railway junction on the Manitoba prairie. Successful in that endeavor, he saw the importance of the Mission junction and invested money to develop the downtown area of what he believed would be another future metropolis. This downtown was on Horne Street, down on the flats by the river. He had buildings put up to create a kind of “instant town”, and he bought great plots of land from the existing settlers. He drew up a map of his plots and divided them into neat lots, naming the streets after cities and states in Canada and the United States. The “Great Land Sale” was advertised in Canada and abroad, inviting potential settlers to buy into his dream. People came by from near and far, and there was a special train to bring people from Vancouver for the day. The St. Mary’s Boys’ Band played and the sale was really quite a spectacular event. However, the auction was less successful than anticipated, and not all of the plots sold. Nevertheless, Horne managed to come out on top. Today, while the streets on his initial map have very different names, three names remind us of his lasting legacy: James, Welton, and Horne Streets are in the heart of downtown Mission.”

Once the excitement had subsided, the mundane reality set in. In a familiar west coast story, many of the buyers of the lots were land investors who lived elsewhere and bought hoping to sell again when the time was right, which left the town virtually undeveloped and empty.

The museum goes on to note that unfortunately, in 1894 the convenience of proximity to the Fraser River became an inconvenience when the river flooded, and the town later had to be re-established further up the hill. His 1892 credit rating was considered to be good – and interestingly he is listed as a rancher on Lulu Island, another of his successful investments.

Mr. A P Horne, who arrived in Vancouver in 1889, and was not a relative of James Welton Horne, remembered meeting him in a conversation recorded by City Archivist Major Matthews in 1945. “Mr. Horne lived down on the corner of about Pender and Howe Street, and used to take his meals at the Hotel Vancouver. So one day I met him at the Hotel Vancouver; he said, ‘Good evening’ as I passed, so I sat down and we talked. He was a fine man. I think Mr. Horne was mixed with Mr. McKee in the street railway, what we call the B.C. Electric Railway now, and there were a lot of IOUs when it got into financial difficulty, and some of them were not Mr. Horne’s, but, as I understand it, he paid the whole lot of them.

“Anyway, we sat on the verandah of the Hotel Vancouver, and we were talking and he told me that he thought a lot of us young Englishmen. He said he didn’t play cricket or football or baseball, but he thought a lot of the young Englishmen who did. He was a very quiet man, I don’t think he belonged to any club; he was so busy looking after his financial interests. I think he married a” [blank]; “they did not live together and I think had agreed to separate.

“He said to me as we sat there that he had no ‘vices.’ Did not smoke or drink; collected his own rents, and had a rule that if the rent was not paid, he would collect 10 per cent extra when it was overdue. So I said to him that he was full of vice; that to charge 10 per cent extra interest was a vice; to collect interest on rent was vice. So I told him how much better it would be if he stopped charging that ten per cent extra on the rent. He told me that evening that he thought he was worth three million.”

Mr Horne lived on into the 1920s, dying in February 1922. His significant assets (which were $209,585 once outstanding accounts had been paid) were divided among his three sisters. Harriet Nelson was born in 1861 in Toronto, was married there in 1884 to Thomas Nelson, and died in Victoria in 1934. Henrietta Sterling was born in April 1863, and died in Vancouver in 1932. It appears that Wilhemina Horne may have married William Mowat in Ontario, but records are poor, and she was apparently known as Wilhemina Horne when she died in Vancouver.

Horne didn’t escape the 1881 census. He’s in Emerson, Manitoba as W. James Horne.

https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?app=Census1881&op=&img&id=e008209845

Thanks. It was 1891 that he seems to have been missed by. (and 1921 as well). We’ve made the edit and tidied up the post a bit.